LIFE WRITING

About

Life Writing is a term that is wonderfully broad, and worryingly vague. At its most productive, it forces us to interrogate what exactly we mean by life, what and who we include and exclude, and, when coupled with the word writing, who or what is worthy of having their life recorded, and what is the relationship between the lives of the inscribers and the lives of the inscribed, or the pact between reader and writer, which Philippe Lejeune identified as the core of autobiographical practice.

The age of social media, the virtual and the digital, has changed the landscape of life writing, a topic I and three colleagues in our School of Languages explored at UCC in the 2011 conference “Technologies of the Self: New Departures in Self-Inscription” which asked how inscription techniques in the age of new media might give rise to new theoretical approaches to autobiography after Lejeune.

In a social media age, we are all proficient self-inscribers. Our carefully curated second lives on Facebook and Instagram illustrate what deft practitioners of the dark arts of self-inscription and self-curation we are. The corollary of this digitally intensified self-inscription is, ironically, that the private life appears to be dead. Which leads one to wonder what the stuff of future biographies and autobiographies will be.

But none of this even begins to do justice to what thinking about Life Writing might involve. The people who have engaged with the cluster so far, either as speakers or as audience respondents, are involved in life writing in many different ways, and it is this plenitude of approaches that will advance the theoretical consideration of Life Writing.

It seems easier to ask what is not life writing than to offer any adequate definition of what it is. Nevertheless, many people at UCC are engaged in projects that come under the auspices of life writing, whether or not they have ever used that term.

A sample of the projects that researchers at UCC have been and are engaged in includes diaristics: our Head of College, historian Chris Williams, is best known for his edited collection of the letters of Richard Burton; Eibhear Walshe of the School of English, whose biography of Kate O’Brien (2006) is an obvious example of Life Writing, has also produced historical fiction, both in his remarkable The Diary of Mary Travers and The Last Day at Bowen’s Court. Another strand of research is political biography, which Women’s Studies’ Elizabeth Kyte is working on currently, looking at the biographies of female Irish Socialists. Similarly, Claire O’Reilly’s fascinating project on Lesser Lives, seeks to inscribe into our intercultural consciousness those historically marginal figures who have been significant nonetheless to Irish-German relations. Then there are our early career researchers, some of whom are here today, whose projects (current and future) suggest other dimensions of life writing that this cluster might foster: Marnina Winkler, a PhD student is researching the papers of former Lord Mayor of Cork, Gerard Goldberg, and through him, looking at Jewish Cork life; James Bačík, whose MA project looked at the contentious topic of Sudeten German lives after the second world war, and new PhD student Dylan Mason who is working with the diaries of Victor Klemperer, asking about the position of this Life Writing on the Modern Languages curriculum. My own work on life writing, is not so much written as silent: it has taken the form of exhibitions, including last year’s exhibition of art about Tuam, where 800 babies, born in an infamous Catholic mother and baby home, still lie, unclaimed in a septic tank. Here, writing lives back into public awareness for the purposes of restorative justice demanded, it seemed, another vocabulary altogether, and one for which, as yet, there are neither proper names nor proper words, including the words of apology. Similarly, the exhibition “afterlives: and how to have one” with Miriam Sachs, Boole Library 2019-20 sought to bring back to life dead authors through subversive acts of facto-fictive intervention, including forgery. We took all sorts of liberties with the lives of dead authors in our reanimations, and this has led to another project of mine, which is the re-gendering of Heinrich von Kleist, asserting that all his works were actually by his physically similar and equally gifted and adventurous sister, Ulrike. This chapter is not yet fully written.

What this cluster might become is also as yet unwritten too: What I hope for it is that its content will be populated by the interests of anyone who wishes to be involved, whether those are creative, theoretical or archival, whether they are questions of how to film a life, how to reinvent a life, how to move life writing into a posthuman age, or how to write the lives of semi- and inanimate objects. It is exciting at this incipient point to imagine where this might go, the unwritten life of this cluster.

If you are interested in making a contribution within this cluster, please contact Rachel MagShamhráin at rmgs@ucc.ie

RECENT AND UPCOMING ACTIVITIES

Seminars and Conferences

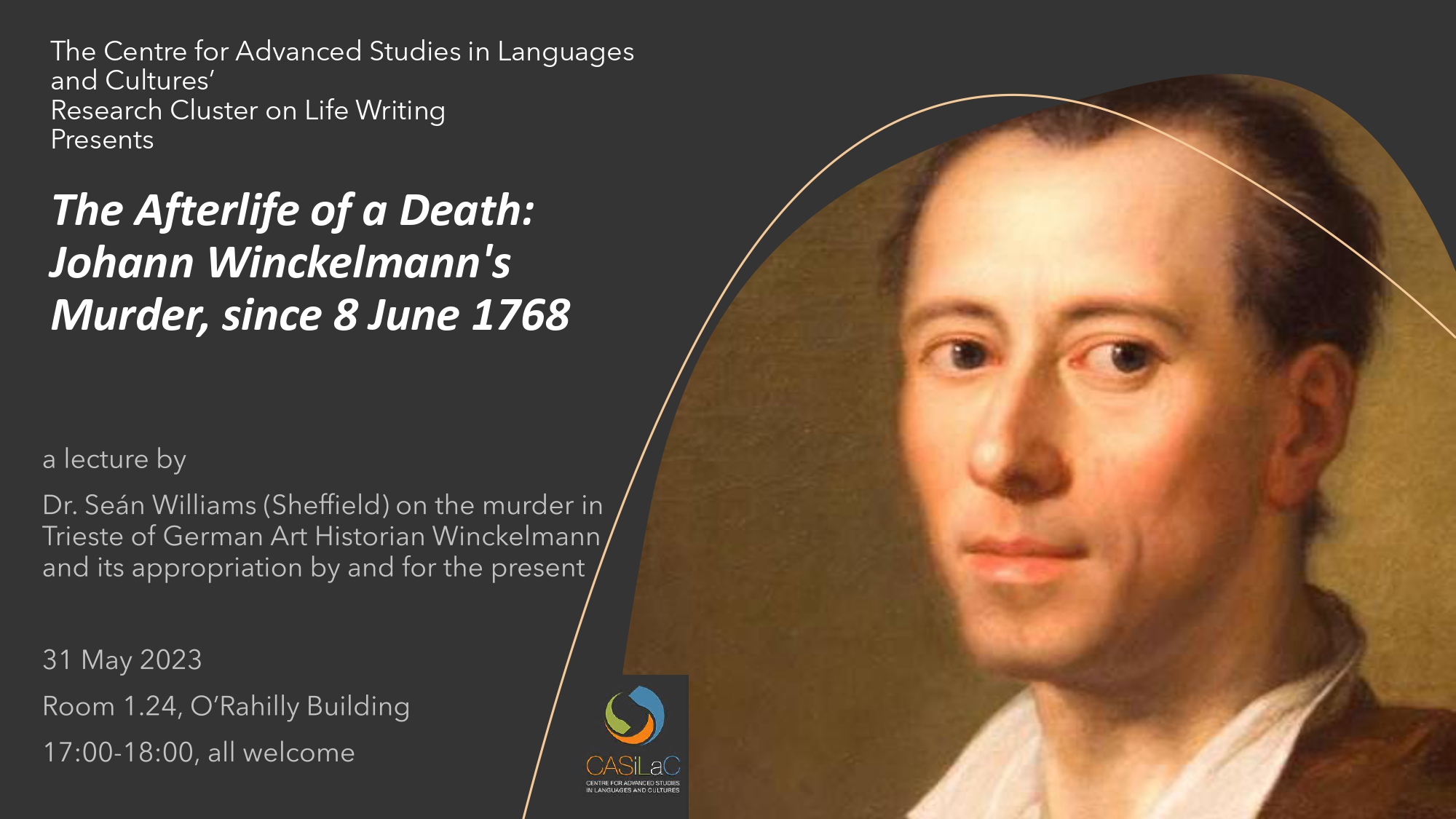

The cluster organises Lectures, Seminars and Conferences. Among the most recent: 31 May 2023 Lecture by Dr. Sean Williams: “The Afterlife of a Death: Johann Winckelmann’s Murder, since 8 June 1768”

Launch of the Cluster

The Life Writing Cluster has been launched on the 5th of November 2020 with a talk by Rebecca Braun (Lancaster University), followed by a work-in-progress paper on Life Writing and the Shoah by Helen Finch (University of Leeds).

Online life-writing discussions: ‘John Banville’s Lives’

In the first of a series of practitioner-led Life-Writing discussions, Irish Novelist and Screenwriter John Banville discusses his work on and with other people’s lives, including in his novels Copernicus and Kepler, and his fictional treatment of Anthony Blunt in Untouchable.